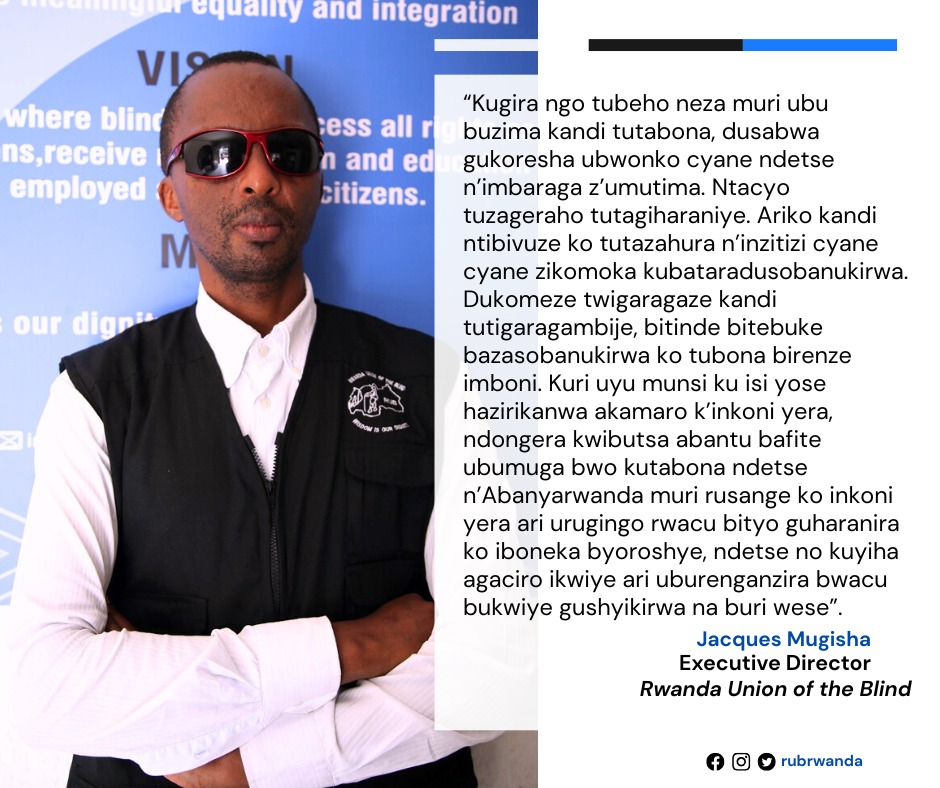

“Seeing Beyond Sight”: Jacques Mugisha’s Message on Dignity, Inclusion, and Climate Awareness

Disability is often misunderstood — reduced to what one cannot do, seen only in terms of limitation. Yet Jacques Mugisha, Executive Director of the Rwanda Union of the Blind, reminds us there is more to the story: dignity, inclusion, respect, and effort.

He reminds us that living without sight does not mean living without purpose or capacity.

“To live well in this life, even without sight, we must use our minds and the strength of our hearts. There is nothing we can achieve without effort,” he says.

Mugisha acknowledges that persons with visual impairments continue to face social barriers — misunderstanding and discrimination among them — but he believes that perseverance and visibility can challenge these perceptions.

“This does not mean that we will not face challenges, especially those linked to being misunderstood or discriminated against. We must continue to show that we are capable and that we see beyond appearances.”

Central to his message is the reminder that inclusion is not charity — it is respect for shared humanity.

“On this day, which is recognized around the world, I remind everyone that persons who are blind or visually impaired, including Rwandans, are part of our shared humanity.”

He adds that the white cane, often viewed only as a symbol of blindness, should instead be recognized as a sign of empowerment and equality — and one that must be available to all who need it.

“The white cane is not a sign of weakness but a symbol of our journey toward visibility, dignity, and inclusion.”

Beyond issues of accessibility and respect, Mugisha draws attention to how the changing climate is creating new challenges for persons with disabilities. He notes that the impacts of climate change are felt by everyone, but those already in vulnerable situations experience them more harshly.

“The effects of climate change reach others, and they also reach us. But because we are already in a more vulnerable situation, the impact becomes even harder.”

For persons with visual impairments, stronger sunlight and extreme weather bring practical difficulties that are often overlooked. Mugisha points out that sunglasses, which help protect against harsh sunlight and eye conditions, are not covered by Rwanda’s community-based health insurance scheme, mutuelle de santé.

“Getting sunglasses is not covered by the mutuelle. Not all of us have the same problems, but many face the challenge of needing sunglasses because of strong sunlight and having eye diseases. Sunglasses are not included in the mutuelle because they are treated as personal accessories rather than medical necessities.”

He also notes that during natural disasters such as floods, persons with disabilities face additional risks.

“When floods or other disasters occur, our members — who are persons with disabilities — cannot always run away quickly or help their families as easily as others without disabilities.”

Mugisha’s words connect everyday experience with a broader truth: inclusion and environmental resilience are inseparable. Ensuring access to essential tools like the white cane, or protective ones like sunglasses, is not a luxury — it’s part of building a society that values every person equally.

His message is both personal and universal — a reminder that progress depends on effort, respect, and the recognition that everyone, regardless of ability, has a place and a role in shaping a sustainable future.

Because, as Mugisha shows through both his message and example, to truly “see beyond sight” is to see the worth, dignity, and potential in us all.

Today, on International White Cane Day, we recognize that the white cane is not merely a tool for navigation but a powerful symbol of independence and dignity for individuals who are blind or visually impaired.

In Rwanda, approximately 86,000 people are legally blind, with cataracts being a leading cause of vision impairment .

Globally, at least 2.2 billion people experience some form of vision impairment, and nearly half of these cases could have been prevented or remain unaddressed .

This day serves as a reminder that access to essential tools like the white cane is not a privilege but a right—one that empowers individuals to navigate the world with confidence and participate fully in society.

Trending Now

Hot Topics

Related Articles

Why Animals Are a Key Piece of Africa’s Disaster Resilience Puzzle

Across Africa, people and animals have coexisted for centuries, not just sharing...

Leaders Call for Stronger Monitoring to Turn Ecosystem Restoration Commitments into Results

Nairobi, Kenya — 27 January 2026 Country and regional leaders, alongside technical...

Worm Tea: A Natural Path to Farming Without Harmful Chemicals

For much of his early farming life, Isaac Mubashankwaya believed chemical fertilizers...

Enroll Now Before 31 December 2025: International German Language Exams Launch in Rwanda

Rwanda will host the European Consortium for the Certificate of Attainment in...

Leave a comment